Arachnids.

Yes, arachnids; our eight-legged ?friends? that cling to the shadowy, forgotten corners of our homes, under the damp seal of a rock, to the harsh, hot crust of the desert, and to their feathery webs, crafted overnight in our gardens. Arachnids, as a group, are not at all unfamiliar to us humans, and while, overall, the relationship between ourselves and these ubiquitous invertebrates is a bit complex, by and large in Western culture, arachnids are feared and reviled. The most familiar groups of arachnids, spiders, scorpions, ticks, and mites, have earned reputations as some of the most terror-inducing, retch-provoking, and spine-shuddering animals we encounter in our day-to-day lives. We cringe at the thought of ticks embedded in our skin, face first, bodies inflating into pulsating balloons of blood. We attempt to ignore the unsettling fact that millions of microscopic mites graze on our dead skin cells, both separated from our bodies and still attached. We regard scorpions, prehistoric beasts made of plates, claws, stingers, and venom, as symbolic of the uninhabitable desert wilderness.

And then, of course, there are the oh-so common spiders, creatures who receive reactions from humans ranging from praise for their beautiful, radial web architecture, to mild annoyance when encountering a surprise face and mouthful of this same web on a forest trail, to revulsion and a swift, life-ending blow with a shoe or newspaper (turning the hapless critter into a drab smear of entrails), to blinding, full-on arachnophobic panic. These last group of arachnids, in particular, are the animal kingdom?s ?black sheep? in our culture, becoming a fixture in our conceptualization of the spooky atmosphere of Halloween; curiously, along with bats, spiders are among the few living, non-fictional entities we set alongside the stereotypical ghoulish folklore characters like zombies, skeletons, witches, and sundry other monsters. Apparently, we consider spiders among the creepiest, darkest, and most unnerving of all living things.Those that fear spiders, and creepy-crawly arachnids in general, cite these creatures? long, spindly limbs, soul-less eyes, hairy bodies, venomous fangs, fast movements, and a tendency to inhabit abandoned, abyssal areas where we are already at unease, as some the reasoning behind their prejudice. This instinctual aversion is strong enough, and prevalent enough, to inspire scores of films and literature where spiders are featured as agents of terror. Seriously. There are plenty. Of examples.?Our overwhelmingly negative view of spiders, especially, obscures some of their talents, many of which are immensely useful to humans. These include the production of a silk that is tougher than Kevlar (which has instigated research into super-strong materials), and an inarguably critical ecological role that keeps populations of their prey items (insects) in check. Spiders, like most arachnids, in the immortal words of Rodney Dangerfield, ?get no respect.?

Oh jeez. Are you guys happy now?

In the same way that spiders and other more familiar arachnids are misunderstood and have unrecognized, underappreciated roles in our lives, the very definition and realization of what arachnids, in the broadest sense,?actually are?typically is met with limited experience and knowledge. For example, most people, if prompted to ?name an arachnid? would answer firstly (overwhelmingly so) with ?spider.? Some might follow up with ?scorpion?, or perhaps ticks and mites?pretty much everything with eight legs and without insect-like antennae that comes to mind. However, the diversity of arachnids extends far beyond the web-bound orb weaver bobbing in the breeze in your front yard?s hedges, or the chigger causing lovely, itchy welts to form on your skin. While these groups are the most speciose, and most common accompaniment to our daily lives (good or bad), there are entire taxonomic orders of arachnids that go quite completely, and miserably, ignored.

This entry is to serve as the first in a series of explorations into the less-loved (or, perhaps, less-persecuted, simply out of unfamiliarity) arachnids.

But first, perhaps it is helpful to start with the following question: what is an arachnid, exactly?

The rule of thumb distinction between insects and arachnids, when trying to broadly identify a little, buggy critter with lots of legs, is the number of limbs, the number of body segments, and the presence or absence of antennae. This diagnostic method tends to work well in practice, but it doesn?t really inform?why?this distinction between the two types of animals is important, and the phylogenetic, evolutionary context.

Firstly, arachnids are members of the phylum Arthropoda (meaning ?jointed leg?). Essentially everything you find on this planet that has an exoskeleton, jointed appendages, and a segmented body is an arthopod; think insects, crabs, centipedes, shrimp, and the extinct trilobites. As far as animals are concerned, the vast bulk of them, both in number of species and number of individuals, are arthropods. There are over a million described species. If you were to randomly select a single species of animal on this planet, four times out of five that species would be an arthopod. When most people think of animals, furry mammals and other vertebrates instantly come to mind, but in reality, Earth is fucking covered in a tide of tiny, robot-like arthopods in all environmental realms.

Within this phylum are subdivisions, called ?sub-phyla? that break up the gargantuan number of arthropod species into about four living groups. One of these groups is the Chelicerata, which includes arachnids, but also includes living fossils like horseshoe crabs (obviously not true, crustacean crabs) and potentially an enigmatic, alien group of animals known as ?sea spiders? (although the classification on this group is constantly in review). It is the arachnids that make up the great majority of chelicerate diversity. Chelicerates are distinguished by the presence of unique pre-mouth appendages known as chelicerae, which have diversified into a wide range of morphologies, including the fangs of spiders, and pincer-like forms in most other members of this clade. Chelicerates also have appendages called pedipalps, which in more primitive groups are leg-like, but in ?higher chelicerates? have been modified into delicate sensory tools, organs used in reproduction, or weapons for defense or procuring food. Pedipalps can, with some reservation, be thought of as the chelicerate version of hands. Tiny, finger-less, hairy, creepy, jointed hands.

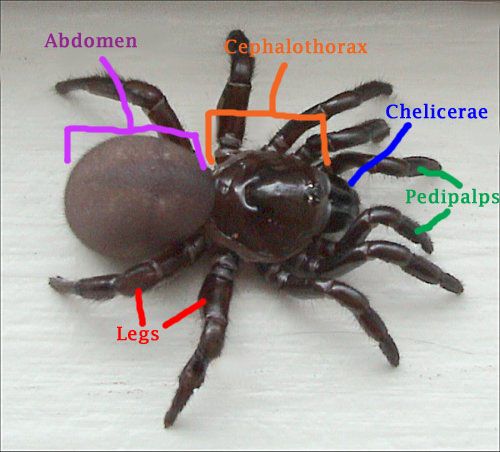

Arachnids, members of the class Arachnida, are the most prominent chelicerates (with more than 100,000 species), and have become by far the most successful group of chelicerate to colonize terrestrial ecosystems. This group, more or less, has two distinct body segments (called ?tagmata?); a cephalothorax (essentially the fusion of the head and thorax, typically covered by an unsegmented carapace), and the abdomen. The separation of these two tagmata can be stark, like in spiders, or more nuanced, like in ticks or scorpions.

Not labeled: Horror genre marketability gland

The distribution of internal organs, and relative position of limbs, in this bi-segmented set-up that the arachnids have going on is a little hard to understand from our own vertebrate perspective. Imagine if you didn?t really have a neck, and your head sort of just continued on into your body, and if your arms and legs attached in this area right behind your head. Now, imagine if everything sort of pinched off behind your legs, and about 90% of all your major organ systems were packed into a bulbous mass sticking out beyond that ?waist? behind your head-legs. Oh, and you wouldn?t really have a ?normal? circulatory system, just a blood-filled cavity that sort of periodically dumped oxygenated blood on the other organs. This is known as an ?open circulatory system? and is typical of arthropods.

You?d be a horrific, human calabash?with limbs?and a hole leading to your lungs where your asshole should be. Your actual?anus would be on your lower back, right above your respiratory hole. So, holding your breath while taking a dump would be recommended. As if that wasn?t bizarre enough, under this configuration, you would have your?genitals positioned on your sternum.?You would probably find it hard to get a date.

Arachnids certainly don?t eat like we do either. The overwhelming majority of arachnid species are carnivorous, and tend to liquefy their prey items by injecting or covering them with digestive enzymes after capture. Only in a small minority of groups is the viscera-smoothie option rejected for the consumption of conventional, solid bits of food.

Reproduction and early life development in arachnids differs significantly from that of insects. Most of this difference comes in the lack of any kind of metamorphosis taking place in the development of young arachnids. Once arachnids are out of the egg, there?s no time for legless, lackadaisical, larval childhoods; they get right with the program and are born with the capacity for rapid movement (and within a short amount of time, the ability to kill food for themselves), being simply small, softer-bodied versions of adult arachnids. Anyone who has come across a mature spider egg sac and poked it with a stick is well-acquainted with the precociousness of hundreds of miniature, ghostly white, pollen grain-like babies, which quite suddenly engage in an exodus from their safe nursery?and onto the stick?and onto your hand.

Of those 100,000 arachnid species, 40,000 are found in the order that contains the spiders (Araneae). Another 30,000 are in the order belonging to mites and ticks (Acari). There are another 2,000 species of scorpion. Three-quarters of arachnid diversity is taken up by these three groups, but there are roughly a dozen orders within the arachnid class, and most of those remaining nine groups have species counts in the low hundreds, and don?t nearly get the publicity or exposure as a common barn spider or a deer tick.

The first of these neglected orders that will be addressed is the order Amblypygi, with its comparatively meager 136 described species. Pronunciation of this order?s name may conjure imagery of a sauntering swine, but the translation from Greek derives its true meaning?which is quite literally ?blunt ass? (amblyo- = dull, blunt, pygo- = rump). It seems like an oddly benign descriptor for an arachnid, especially when it?s for the entire taxonomic order. Perhaps, you think, it?s a stumpy, adorable sort of thing; the rare ?cute? arachnid. Surely, you say, that?s what the ?blunt butted? Amblypygi must consist of.

You were wrong.

This unholy combination of legs, spines, and the tears of small children is known as a ?tailless whip scorpion?, as well as a ?whip spider?, although it is neither a scorpion or a spider and is obviously far more terrifying than either of those things. This twisted creature appears to be molded out of the most unsettling portions of spiders, praying mantises, crabs, and daddy longlegs, but through the curious gestalt properties, is a uniquely hideous product of nature. You may recognize these animals as the ?spider? that was used in demonstration of the ?three unforgivable curses? in this scene in the film adaptation of ?Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire??or, alternatively, in the worst dream you?ve ever had.

The ?whip? part of the name comes its first pair of legs, which have been modified into elongated, highly-sensitive, antennae-like probes. It is tempting to hypothesize that the function of these whips is for tickling the nose of sleeping humans so that they?ll open their mouths, allowing for this charmer to climb inside and lay its eggs in the back of the throat? but this is, fortunately, not the case. The whips are instead sensory organs, held far out in front of its body in order to detect anything worth snatching up for a meal. This includes crickets, beetles, caterpillars, and firstborn Egyptian sons.

It achieves this by use of its pedipalps, which you may have noticed have been modified into vicious, raptorial claws (?raptorial? typically referring to a limb that has underwent modifications for grasping prey). These long pedipalps, whose ends are densely studded with sharp, interlocking thorns, are kept tightly folded up against the gnashing chelicerae of the amblypygid, patiently awaiting some incredibly unlucky insect to cross its path. The pedipalps are also used in territorial displays against others of the same species, and amblypygids routinely extend and clash them against those of a transgressing individual (like bucks do with their antlers) in order to persuade them to step off their turf, whether their neighborhood is rich in mates or in prey.

That sound you?re hearing is your bladder involuntarily emptying itself.

However, unless you are living in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world, you are unlikely to come across an amblypygid. Even if you were a resident of these warmer latitudes, you?d still have to search for these guys. They are usually nocturnal creatures, preferring to wedge their flattened bodies underneath wet logs, stones, or a piece of tree bark during the day?places where you really shouldn?t be putting your hands anyways while in the tropics. At night, they move silently and carefully along the rainforest floor, surveying their world by way of the delicate touch of their sensory legs. This is really the only way for them to interact with their environment, because amblypygids are really fucking blind. This may be a little surprising, considering that they have eight eyes; three grouped together on each side of the cephalothorax, and two more right in front on that raised bump that looks a bit like a nose.

If you were to somehow come across an amblypygid in the wild, you would have little to worry about. I can hear your incredulous gasps now, ?What? How can this be??Look?at this thing!? Amblypygids generally resemble what would come skittering out from between the dank, unwashed folds of a nightmare. They look like the voracious guardians of an ancient, booby trapped tomb in an Indiana Jones movie, or something that would hitch a ride across the galaxy on an asteroid, only to collide with Earth, scuttle out of the impact crater, and seek to take over the planet. If there was an organism banished to inhabiting the dark, dusty, cramped, lonely unknown of the area behind your washing machine, it would be an amblypygid. Surely, you protest, this spindly troglobitic creature, with its horrible claws, beady eyes, and all-feeling whips, bound to darkness and the humid, alien, subterranean world just below the forest undergrowth?must be deadly. Indeed, it must be a rabid, bloodthirsty monster; fangs overflowing with venom, legs taut with the anticipation of leaping and clinging to your face, spiky pedipalps itching to spring wide open and impart a puncturing embrace.

While the imagery of a company of ill-fated cave divers being feasted upon by hoardes of hyperaggressive, dinner plate-sized demon-spiders might seem appropriate for an animal as unsettling in aesthetics as the amblypygid (or for a low-budget, made-for-TV thriller; I?m looking at you Syfy)?but in reality, this scenario is an impossibility.

Observe, the horror that is an interaction between a human and a large amblypygid:

The person handling the amblypygid in the video above is by no means brave (so stop being impressed). The truth is, amblypygids are about as harmless as it gets for an arachnid. Their chelicerae are not the hollow, venom-engorged tubes found in the spiders, and the most danger to a human that comes from an amblypygid nip is a small amount of transient pain; like a mosquito bite with less itching. Just getting an amblypygid to engage in such behavior requires a great deal of pestering, as these creatures uniformly flee and seek refuge in tight, hard-to-access areas at the first annoyance. Defensive retaliation, a very rare occurrence, usually takes the form of a strike with those prickly pedipalps. This is kind of like getting smacked with a nail-bat?but with one only a couple inches long, probably doing about as much damage as a light brush with a thorny blackberry vine. Put simply, if an amblypygid decides to be uncharacteristically feisty with you, I?m pretty sure you?ll live.

Because of their docile temperament, combined with their intimidating appearance and size (some species can have leg-spans significantly wider than a human hand) amblypygids are reasonably popular as pets. Many other similarly-sized arachnids, like tarantulas and some larger scorpions, have a very real capacity to do some harm if handled improperly and/or given the opportunity to become aggressive. For example, some species of tarantula (only found in the New World), if threatened, will take a hind leg and quickly rub the top of the abdomen, kicking up a cloud of urticating hairs. These tiny, barbed hairs are incredibly irritating to human skin and mucous membranes, and if inhaled can cause potentially dangerous levels of airway inflammation; if the sharp hairs get embedded in the eyes, there is a substantial risk of partial or temporary blindness. Tarantulas can also plunge those giant fangs into human flesh as a defense mechanism, although this is rare. Unlike a nibble from the weak chelicerae of an amblypygid, a tarantula bite is not a walk in the park. You won?t die or get sick from the venom, but the sensation is a bit like being stabbed with a freshly sharpened pencil?on fire. Also, in the days following, the area of the bite swells up into a tender bubble of misery.

Scorpions, of course, have a whole suite of painful/deadly tools they can use on humans that I don?t think I need to go over.

Amblypygids easily achieve the ?wow? factor held by these other common arachnid pets (and then some), and bypass all of the risk of harm or death associated with ownership and handling.

We tend to view arachnids, and other exoskeletal, creepy-crawlies, as unthinking, anti-social automatons whose only function is to eat, avoid being eaten, and to make more of themselves. Often times, this assessment is somewhat accurate. Hell, the female representatives of many arthopod species (like spiders and praying mantises) routinely wolf down their bite-sized lovers without even batting a compound eye?because apparently that?s your only available post-coitus activity if you?re smaller than a cigarette. Some insects, like ants, termites, wasps, etc., form highly hierarchical societies and massive colonies of interdependent individuals, but this is an exception to the general rule in inter-arthropod relations. Tending to and caring for offspring beyond the egg stage isn?t ?a standard behavior, and communication between mothers (I say ?mother? because ?father? is probably currently in the process of being digested by ?mother?) and offspring is certainly limited. Let me put it this way: ?good parenting skills? in arthropod households typically consist of refraining from immediately eating more than half of your hatchlings?and that?s about it. There?s no way to get around it; arachnids and other arthropods are a cold, sociopathic bunch.

It may surprise you, given their off-putting, emotionless exteriors, that amblypygids are among the most socially savvy of all arachnid groups. Beneath that stiff, hard exoskeleton, amblypygids are, both literally and figuratively, big ol? softies.

While allowing newly-hatched young to piggyback for a little while is found in some arachnids (scorpions and some spiders do this, for example), the amount of care and interaction that amblypygids give their relatives is unusually high by arachnid standards.

One-upping soccer moms for 400 million years

Research from entomologists at Cornell a few years back?on two species of amblypygid revealed that familial interaction in these arachnids might extend far beyond simple motherly protection and transport for squishy newborns. For example, mothers in these species keep their young (I like to call them ?amblypyg kids?) close by long after they were able to fend for themselves and get around on their own. Throughout the young?s pre-adult development, their mother caresses them with her sensitive whip legs, and the young reciprocate with their own sensory appendages. The young also interact with each other in this way; constantly petting each other with their whips. It?s as if they do this to soothe each other.

Yes, the scary, nasty-looking amblypygid is a cuddler.

Perhaps most strikingly, the young siblings of these species organize themselves into social groups all the way until reaching sexual maturity, which then immediately leads to combative, aggressive behavior towards each other. Anyone who experienced their teen years with siblings can probably identify with this phenomenon.

Up until this developmental stage (amblypygid puberty occurs roughly a year into their lives), the bonds formed between siblings and their mother are steadfast. If scattered and dropped into unfamiliar territory, the siblings feel around and seek each other out until they all re-group into one, big, happy family again. Of course, once the gonads kick into gear, family reunions result in unrepentant cannibalism. But, until then, brotherly and sisterly love are plentiful in an amblypygid?s world.

So, this concludes the introduction into one of the less acknowledged and less understood orders of arachnids. Despite their appearance, you certainly can?t judge amblypygids by their cover. For all their demonic homeliness and menacing first impressions, amblypygids are among the most amorous of the class Arachnida, both towards giant primates like ourselves, and uniquely towards members of their own brood. Perhaps if an animal with a brain smaller than a period on this page can learn to care for, and appreciate, other individuals in its species, we can somehow manage to do the same.

Image credits: Opening spider photo, source for arachnid diagram, Amblypygid #1, Amblypygid #2.

? Jacob Buehler and ?Shit You Didn?t Know About Biology?, 2012-2013. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog?s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Jacob Buehler and ?Shit You Didn?t Know About Biology? with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Like this:

Loading...

Source: http://sydkab.wordpress.com/2013/02/23/arachnids-amblypygids-2/

january jones ncaa final game reba mcentire acm awards the killing april fools global payments

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.